Telehealth

In the world of telehealth, there are a lot of terms that sound similar, but they're not synonymous. Understanding the differences between these terms is key to understanding the field, particularly as it relates to the legal questions that a lot of us have. This isn't an exhaustive list, but here are three of the most important terms to grasp:

For more information, check out: AVMA: Telehealth Basics

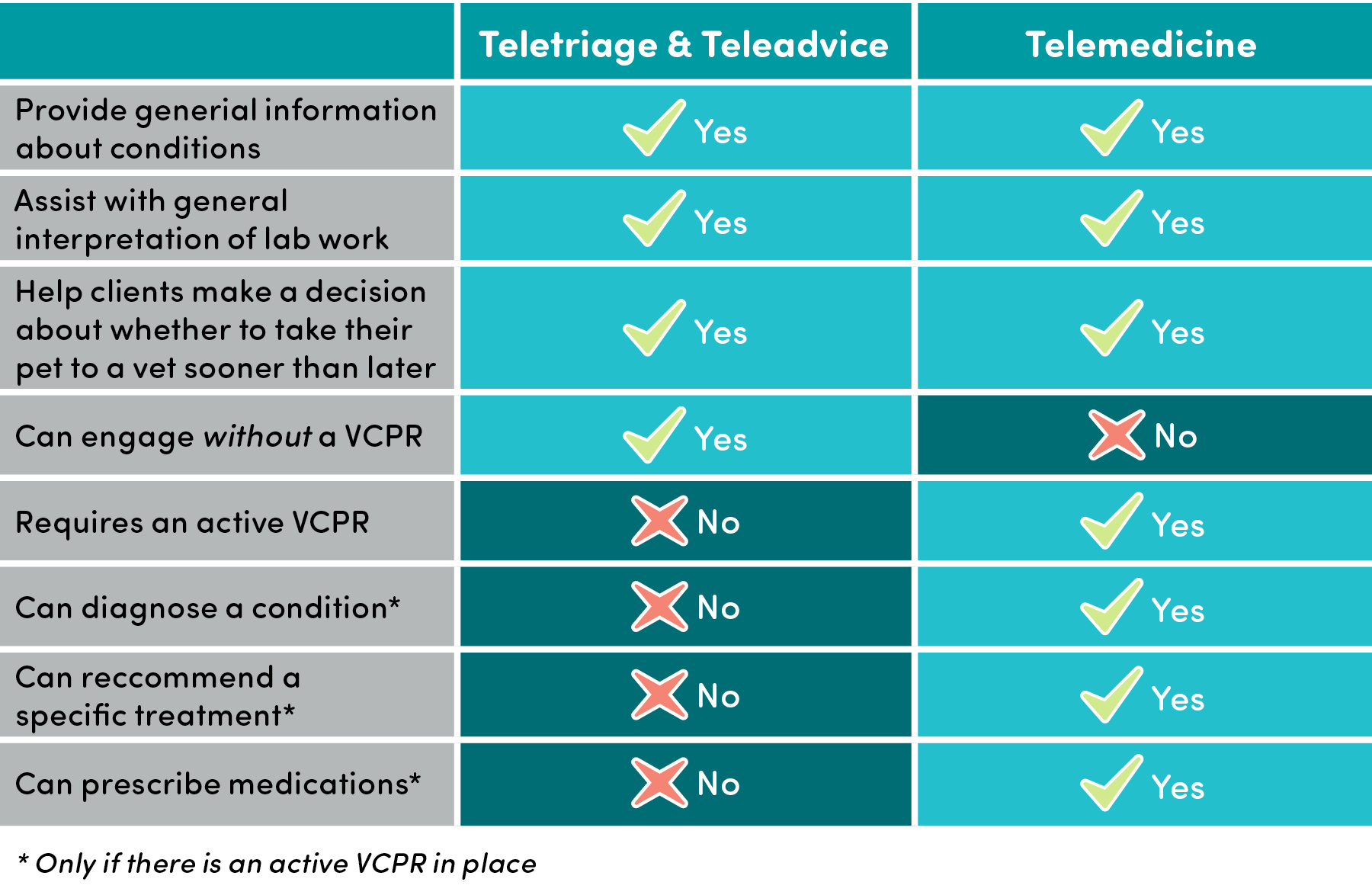

Definitions Chart

For any questions pertaining to legality, it is important to consult your state's veterinary practice act. You can also call your state's veterinary boards directly. To do so, you can usually simply do a web search for "[your state] veterinary practice act" and find it. A lot of the questions of legality surround the idea of a "veterinary-client-patient relationship" (VCPR). Check out some of the following questions for more on that.

This is another area that varies on a state-by-state basis and can often vary depending on the specific emergency. It is important to check your state veterinary board and/or practice act.

The definition of a VCPR varies slightly from state to state. In most states, a VCPR exists when a veterinarian has seen the pet in person, has access to the pet's medical history, and enough working knowledge of the patient to provide at least a general diagnosis. For more information:

This is a particularly difficult question to answer. Few states - if any - give a precise answer to this question, nor does the American Veterinary Medical Association. You will often see phrases like, "...veterinarian must have performed a timely examination...". These sorts of phrases are intentionally vague, allowing the veterinarian to use his or her professional judgment.

This is another situation that is rarely, if ever, clearly described. Some shelter veterinarians look to farm animal veterinarians as a model for this situation. Farm animal veterinarians are generally not required to have as VCPR with every animal on a farm, but instead must have an established relationship with the population and the farmer in which they have visited the farm and have a working knowledge of the farm's protocols and practices. Again, check with your state's veterinary board to be absolutely sure.

Setting up a basic telemedicine service at your shelter or rescue is actually pretty simple. Of course, you will need to have an established relationship with a veterinarian who is ready to take this on. Next, you'll need each of the following; an online scheduling system (not necessary but helpful), and a web-based method to keep records of calls.

The details for setting up a system varies according to your needs and whatever technology you may already have in place or be familiar with. But here are the basics and some examples of user-friendly tech options. Again, you don't need every single one of these components.

Nope! There are a ton of available options for free web-based phone numbers that can be routed to your phone but give you an alternative phone number. Check out the options listed above or any others you might already be familiar with.

There are now several commercially available teleadvice/teletriage services. These 24/7 services may be useful to your shelter or rescue. For foster caregivers, these services help take some pressure off of the veterinary and foster coordination staff. If your shelter does not have a vet, shelter staff can use these services for timely advice. Check out some of the following:

Prior to joining the team at Maddie's Fund, Dr. Mike served as program director for Target Zero, helping communities across the US achieve 90% or greater live release rates from their animal shelter systems through implementation of best practice strategies. Following veterinary school, Mike worked in rural private practice. It was there that he began volunteering with shelters and working with shelter staff and leaders to address community issues to increase lifesaving. Having caught "the bug," Mike took the plunge into the sheltering world, and completed his training in shelter medicine with the Maddie's® Shelter Medicine Program at Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine in 2011. Since that time, he has worked clinically and as a consultant for multiple public and private animal shelters throughout the United States. He is based in Nashville, TN where he helped to start Pet Community Center, a shelter intake prevention organization.